Stroke is one of the main causes of long-term disabilities among adults. Depending on the severity and location of the stroke, survivors may present very differently from one another. For instance, strokes of the middle cerebral artery (mca stroke) in the brain result in weakness primarily in the upper extremity, while anterior cerebral artery strokes usually affect the lower extremity more.

A stroke in the brainstem or cerebellum can affect coordination and motor control on the same or both sides of the body. This is because blood vessels supply specific regions of the brain that are responsible for different functions or parts of the body. This makes every stroke unique even when they may share some similar symptoms.

The hand has a complex structure with a broad cortical representation in the motor area. Sophisticated neural circuits control hand function, underlying its indispensable role in patients’ functional independence.

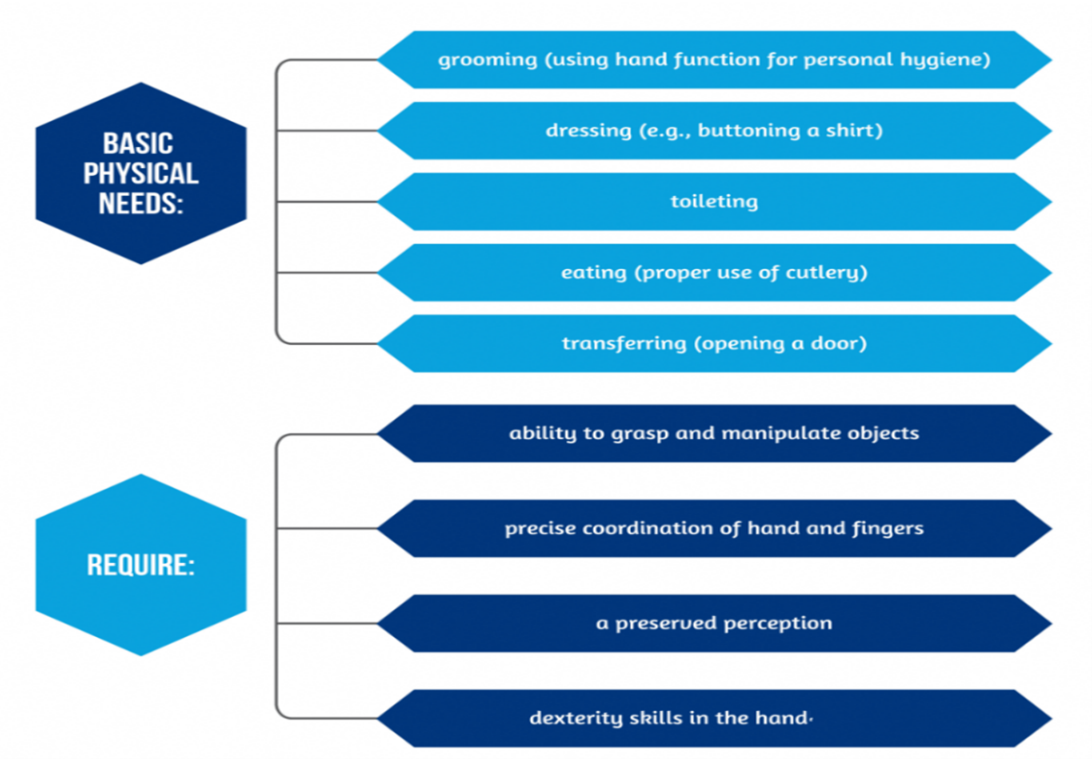

Afferent somatosensory impulses (tactile and proprioception sensations) and input from the primary somatosensory parietal area are key factors controlling precise hand movements. Patients with sensory impairments, which are also common after stroke, have poor performance in dexterity during object manipulation Hand function is often one of the slowest to return after stroke.

Since the hands and feet are distal to (far away from) the midline of your body, this means they are also located farthest from the brain and spinal cord. This increases the distance nerve signals must travel to communicate. Following a stroke, this communication is often delayed or inhibited, resulting in decreased hand function.

Cortico-spinal tract (CST) lesions are common in stroke and are correlated with impairments in fine control of hand movements. The CST has an essential role in precise motor control, such as grip force and individual finger movements. If the integrity of CST is partially preserved after stroke, as demonstrated by the values of motor evoked potentials, studies showed motor improvements in hand function. Other neural substrates and pathways involved in the hand rehabilitation process, are The reticulospinal tract, The basal ganglia circuits, The cortico cortical loops, The somatosensory system.

In stroke patients, sensorimotor upper limb deficits are correlated with a major disability, and the distal part of the hand is usually more severely affected. Manipulation of objects, grip precision, and coordinated finger movements are severely impaired. Impaired hand function is one of the most frequently persisting consequences of stroke. Paralysis of the hand or upper limb occurs acutely in up to 87% of all stroke survivors. Some recovery of motor control after a stroke is typical, occurring most rapidly during the first 3 months and usually plateauing by 6 months. Yet, 40% to 80% of all stroke survivors have incomplete functional recovery of the upper extremity at 3 to 6 months post-stroke.

The brain’s “critical period” for stroke recovery works much like a developing brain’s heightened plasticity. Research shows the brain responds exceptionally well to therapy about 60 to 90 days after stroke. This window lets neural connections form and grow stronger more easily.

The top 5 evidence-based treatments for improving hand function after stroke:

What it is:

Constraint-Induced Movement Therapy (CIMT) is the most researched and proven model of high-intensity stroke rehabilitation. It gives us valuable insights about how neuroplasticity principles work in clinical practice.

There are two key components: constraint and shaping.

Constraint refers to the way in which the hand is restricted. Therapists have used casts, splints, and mitts to restrict the use of the non-affected hand. None of them have been shown to be more effective than the other.

Shaping involves repetitive movements or activities at the patient’s ability level which become progressively harder. Therapists use shaping techniques to avoid overwhelming the motor system.

Who it’s for:

This approach is used for people who have at least 10 degrees of active wrist and finger extension, as well as 10 degrees of thumb abduction (the ability of the thumb to move out of the palm).

It’s been shown to be effective even years after stroke. Lower intensity CIMT is better than higher intensity in the very early stages after stroke.

Mental practice often described as Motor Imagery or Mental Imagery involves an individual visualising performing a task or any bodily movement without having to physically perform it and thus resulting in stimulation of the neural system.

How does it work?

Mental practice is an addition to standard therapy. It can improve arm function and is recommended in the Royal College of Physicians Clinical Guidelines for Stroke (2023) and the NICE guidelines (2023). When you move your hand, you use certain areas of your brain. When you practice moving your hand in your mind, you use the same areas of your brain.

If you do not use your arm, the neural circuits in your brain will weaken. This will mean that over time you lose the ability to use it. This is called learned non-use. Practicing tasks in your mind can make your neural circuits stronger. This may stop you losing movement. You can recover movement through neuroplasticity. This is the brains ability to re-wire and learn new tasks by doing repetitive activities.

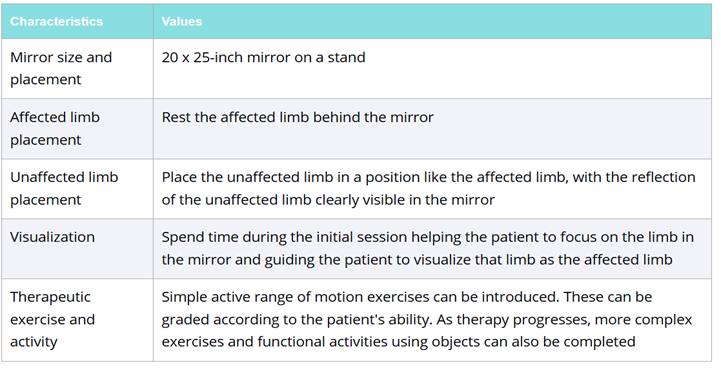

Mirror therapy involves placing a mirror between the hands so that the reflection of the healthy hand appears where the affected hand would be. As the patient moves the healthy hand, the brain perceives both hands moving, which can help reconnect neural pathways that were disrupted by the stroke. This technique is often used to improve hand function, reduce pain, and even decrease feelings of neglect in the affected limb.

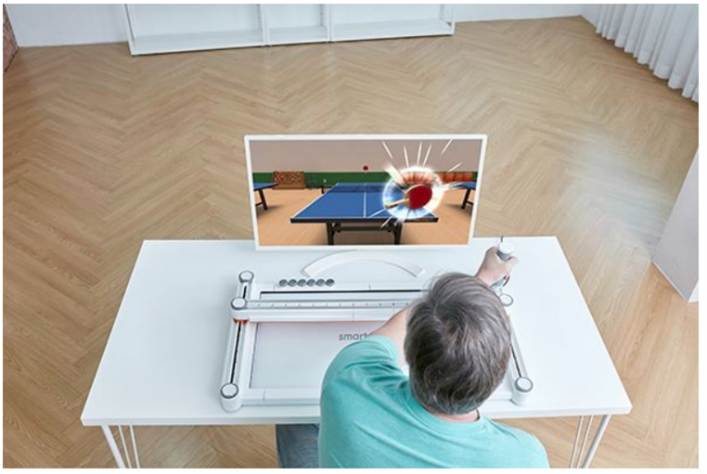

Virtual Reality (VR) is theorized to overcome these limitations particularly those of cost and time constraints. VR is defined as “a computer rendered, 3-dimensional, real-time, interactive experience of artificial reality containing items, characters, and events existing only in the memory of a computer”. It’s become an increasingly more prevalent rehabilitation technique to provide motivation and engagement in therapy.

There are two types:

Why it works:

Virtual reality works best when paired with traditional therapy. It's theorized to provide more motivation and engagement for the intensity of therapeutic exercise needed for neuroplasticity. It's been shown to beneficial in high doses, meaning more than 20 hours.

Virtual reality also creates a biofeedback loop: your brain sends a signal to the muscle, the brain receives a signal back in the form of visual or auditory input. Basically, you get rewarded for your effort.

Repetitive task training works in multiple ways. Regular motor practice reduces muscle weakness and spasticity. It also creates the physiological foundation for motor learning. Sensorimotor coupling helps adapt and recover neuronal pathways. The brain builds new neural connections through repetition that can bypass damaged areas and restore function.

The timing of high-repetition therapy makes a big difference. Animal model studies have showed that the most important recovery advances happen during a short window of increased neuroplasticity after stroke. This critical period offers the best environment for neuroplastic changes and functional recovery.

A detailed review of over thirty trials showed that repetitive task training improved arm function, hand function, and lower limb capabilities.

The most compelling evidence comes from a study of very high-dose therapy (90 hours over 3 weeks). It showed significant immediate gains and continued improvement after therapy ended. Six months after therapy, 61.6% of patients had exceeded clinically important difference thresholds. This proves that intensive therapy can create lasting benefits.